Celebrate Women Everyday

As Women's History Month comes to an end, some may feel the need to move on to the next popular hashtag of the month. It is imperative that we continue to teach and emphasize the power women possess. Women's achievements and strengths should be celebrated every month all year long.

Here at CWC we celebrate the accomplishments of Black women every chance we get! Without the power and perseverance of Black women, fashion would be nowhere near where it is today. They had to navigate a male dominated world, not only as women, but Black women.

Having two -strikes against them from birth didn't stop any of these pioneers from achieving their dreams and doing it their way. As with most industries in America, for many decades Black people were not allowed to run their own fashion enterprises. And when they were granted access to sell their own creations, obtaining business loans often proved near impossible.

Even when a Black Designer finally broke through and designed a wedding dress for the president's future wife, news outlets referred to her as “the colored designer.” Not giving Black women designers any credit or marketing was commonplace in America, and still they succeeded in making a lasting, profound impact on the world, and will be remembered forever.

Lets celebrate Black Women who advanced the fashion industry and continue to inspire us everyday.

Elizabeth Keckly

Elizabeth Keckley was born in Virginia in 1818. She was the child of a forced sexual relationship between her mother, Agnes, and Agnes’s enslaver, Colonel Amistad Burwell. Although she was half white, Elizabeth inherited the status of an enslaved person from her mother.

Elizabeth Keckley

Elizabeth persisted to buy her freedom and in 1852 her enslavers set a price at $1,200 for her and her sons freedom, about $40,000 today. Elizabeth had no way of earning the money because all of her income from dressmaking belonged to the slavers. Many of Elizabeth’s clients donated to her freedom fund and on November 15, 1855 she bought their freedom.

Now a free Black woman, Elizabeth worked as a dressmaker in St. Louis for the next five years. With her earnings, she paid back every person who had donated to her freedom fund. She then moved to DC and when the Lincoln family arrived in the White House, first Lady Mary Todd Lincoln needed a dressmaker. One of Elizabeth’s clients recommended her to the First Lady, who was very impressed with her work. Elizabeth eventually became Mary’s personal dressmaker and stylist.

Elizabeth Keckley’s Designs

Over the next four years, she also became a close friend and confidant of Mary. She went from Slavery to Fashion Entrepreneur!

Lois K. Alexander-Lane

Born July 11, 1916, in Little Rock, Arkansas, Lois Marie Kindle got her start in fashion by sewing dresses for her dolls and eventually sewing for her mother and sisters. As a young girl she would look in boutique store windows and sketch the clothes she liked. Alexander was clearly gifted, but not allowed to go in the stores to buy anything because of her race.

Lois K. Alexander-Lane

While studying for her Master’s degree at New York University one of her professors said that Blacks had not made any contributions to the fashion world. This further lit her fire as she set out to dispel the myth that Blacks were new found talent in the fashion industry.

Although she was a designer her legacy is tied to her efforts to bring more attention and recognition to other Black designers by establishing the Black Fashion Museum.

She opened two custom wear boutiques - one in Washington, DC (The Needle Nook) and one in New York City (Lois K. Alexander & Co.).

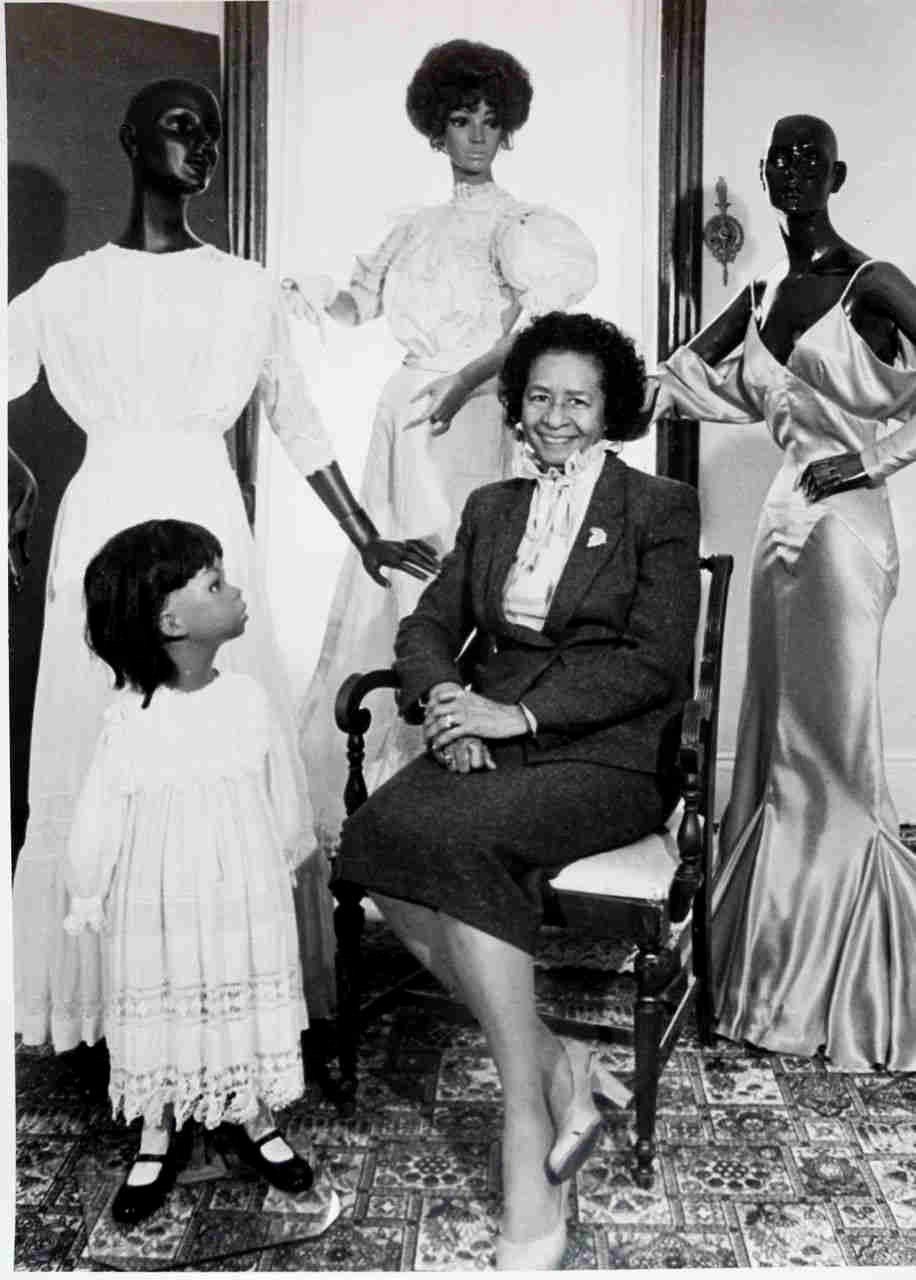

Lois K. Alexander-Lane

Lois K. Alexander-Lane

In 1966, she founded the Harlem Institute of Fashion, an educational institute that offered free courses to students interested in dressmaking, millinery, and tailoring. In the same year she founded the National Association of Milliners, Dressmakers and Tailors.

In 1979, she founded The Black Fashion Museum (BFM) in New York City, committing the rest of her life to telling the world about the centuries of contributions women and men of the African Diaspora have made to fashion and design.

Zelda Wynn Valdes

More than a half century before the “curvy” model became popular, and before the body positivity movement, Valdes knew it was the job of clothes to fit the woman, not vice versa.

Zelda Wynn Valdes

The eldest of seven children, Valdes (born as Zelda Christian Barbour) was raised in Chambersburg, Pennsylvania. She learned how to sew from watching her grandmother’s seamstress. Beginning in 1935, she had her own dressmaking business in White Plains, New York and in 1948, Valdes opened her own boutique, called Chez Zelda in New York City. This made her the first Black person to own a store on Broadway in Manhattan!

In her store, she sold her signature low-cut, body hugging gowns, which unapologetically extenuated women's bodies. Valdes’ sexy-but-sophisticated dresses were worn and loved by Josephine Baker, Diahann Carroll, Dorothy Dandridge, Ruby Dee, Eartha Kitt, Marlene Dietrich, and Mae West.

Singer Joyce Bryant in one of Valdes’s signature designs

Zelda Wynn Valdes

In the 1960s, Valdes directed the Fashion and Design Workshop of the Harlem Youth Opportunities Unlimited and Associated Community Teams. Valdes also taught costume designing and facilitated fabric donations to students in Harlem.

She is also known for creating the infamous Playboy bunny suit, commissioned by Hugh Hefner.

Helen Williams-Jackson

A pioneer in the world of modeling, Helen Williams-Jackson is credited with paving the way for Black fashion models, particularly dark-skinned models.

Helen Williams-Jackson

Born in East Riverton, New Jersey in 1937, Helen was always excited about fashion. Her introduction into the industry came as a stylist in a photography studio in New York. There a photographer convinced her to get in front of the camera. Her career began as an exclusive model for magazines such as Ebony and Jet. However, the discrimination she faced in America as an Black Dark Skinned model led her to relocate to France in 1960, where she found success modeling for designers such as Christian Dior and Jean Dessès.

After Paris, Williams returned to America, where things had not changed for dark-skinned African American models. While searching for a new agent in New York City, she once waited two hours in the reception of one agency, only to be told that they had “one black model already, thanks.”

Undeterred at being rejected, Williams took her case to the press. Influential white journalists Dorothy Kilgallen and Earl Wilson took up her cause, drawing attention to beauty’s continuing exclusion of black fashion models. This opened things up for Williams, who was then booked for a flurry of ads for brands such as Budweiser, Loom Togs, and Modess, which crossed over for the first time into the mainstream press, in titles such as The New York Times, Life and Redbook. Williams’s success broke the tradition for only using light-skinned models.

Helen Williams-Jackson in a Bulova ad

Helen Williams-Jackson in a Budweiser ad

Helen retired from modeling in 1970, but she didn’t leave the fashion industry. She went back to styling and worked for such household names as JC Penney and Sears. She also started a company, H & H Fashions, with friend and photographer, Henry Castro.

Ann Lowe

Considered one of America’s most significant designers, Ann Lowe was born in Clayton, Alabama, in 1898. She spent a few years in segregated schools before leaving to pursue dressmaking, following in her grandmother and mothers footsteps. At the age of 16, following her mother’s untimely death, Lowe took over the family business. She also spent a brief time studying design in New York.

Ann Lowe

In 1953 she designed future president John F Kennedy’s bride Jacluqines wedding dress. Initially she wasn't properly credited for her work, being called “the colored designer” in a NewYork Post article.

Though American journalists didn't appreciate her work at the time, her work was admired by Christian Dior and by the costumer Edith Head. Lowe said that her greatest motivation was simply “to prove that a Negro can become a major dress designer.” It’s thanks to the efforts of collectors and scholars of Black fashion history that Lowe’s impact has become more recognized over the past decades.

One of Ann Lowe’s designs

Ann Lowe adjusts the bodice of a gown worn by Alice Baker in 1962

It shouldn't take a special month out of the year to celebrate these women's accomplishments. They should be recognized anytime for the foundation they laid for us. Black women face a unique struggle that only they experience, and they still fight and accomplish marvelous feats.

Resilience and courage is something that’s baked into the skin of every Black woman.

#womenshistorymontheverymonth